Hello friends,

I’ve just returned from a week in Washington DC where I spent a few days at the Folger Shakespeare Library followed by a few days at my all-time favorite conference, the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America. I would say that it’s like Comic Con for Shakespeareans but there’s a lot less cosplay (no, we’re not a Ren Faire) and a lot more intellectually crunchy panels featuring the newest scholarship by brilliant scholars in the field. Some people in my position would, I’m sure, not be so invested in attending an academic conference that they spent the night before their first chemo treatment completing the paper in time for the participation deadline (perhaps the most on-brand thing I have ever done). They’re occasions that we often grouse about, after all: the timing is bad; the flights and hotels are expensive; the schedule is too packed; the program doesn’t have what we want on it; we have to grade/prepare lessons/do admin work when we get home. Admittedly, this is a more fun conference than many and I see a lot less general grumpiness about it than some I could name (*cough* MLA *cough*). It does share a little bit of the carnival atmosphere of Comic Con, culminating in a dance on the last night that could feel hokey (and does to some people…the conference is divided pretty sharply between dance-attenders and dance non-attenders) but which gives me the kind of warm feelings of kinship that you get from dancing at a wedding. Like: ah, nerdy as they are, this is my family.

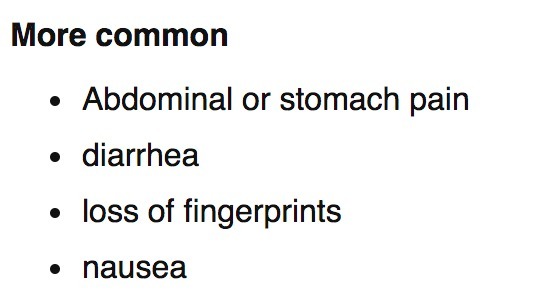

I’ve just returned from a week in Washington DC where I spent a few days at the Folger Shakespeare Library followed by a few days at my all-time favorite conference, the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America. I would say that it’s like Comic Con for Shakespeareans but there’s a lot less cosplay (no, we’re not a Ren Faire) and a lot more intellectually crunchy panels featuring the newest scholarship by brilliant scholars in the field. Some people in my position would, I’m sure, not be so invested in attending an academic conference that they spent the night before their first chemo treatment completing the paper in time for the participation deadline (perhaps the most on-brand thing I have ever done). They’re occasions that we often grouse about, after all: the timing is bad; the flights and hotels are expensive; the schedule is too packed; the program doesn’t have what we want on it; we have to grade/prepare lessons/do admin work when we get home. Admittedly, this is a more fun conference than many and I see a lot less general grumpiness about it than some I could name (*cough* MLA *cough*). It does share a little bit of the carnival atmosphere of Comic Con, culminating in a dance on the last night that could feel hokey (and does to some people…the conference is divided pretty sharply between dance-attenders and dance non-attenders) but which gives me the kind of warm feelings of kinship that you get from dancing at a wedding. Like: ah, nerdy as they are, this is my family.

Perhaps this trip was kind of a weird thing for someone with Stage 4 cancer to be doing. I have, potentially, precious little time in this world (even in the best case scenario it’s far less time than I’d anticipated) so why spend so much of it on work? The simple answer is that, with less time, it has become all the more important to spend it doing the things that make me feel the most like myself. And that means a trip to a rare books library where I can spend 8 hours a day combing through 400-year-old plays in search of annotations. It means doing a survey cross-indexing my list of plays against the library catalog while listening to all the Girl Talk albums in succession. It means the giddy satisfaction of closing out the library and going to happy hour with my fellow researchers. It means 10-hour conference days where I work hard and play hard and take copious notes in appreciation of my friends’ and colleagues’ fantastic minds (and maybe sneak a nap in my hotel room during the late-afternoon slump). And it means closing out the weekend with a community that has stepped up in incredible support of me in the time since I’ve made my diagnosis public in a way I did not expect and am profoundly grateful for - a fact which is the point of this post.

I found myself in the hotel bar somewhere in the neighborhood of 2am on Sunday morning, quite literally weak in the knees from so much dancing, guzzling water and keeping company with colleagues who I’ve come to call friends as we all, exhaustedly, said repeatedly “we should go to bed” and subsequently did not. There was a real last-day-of-camp vibe that infused the whole thing with preemptive nostalgia for the time–so soon!–when we would not be together in the same place. This is the thing about assembling in person only for a few days every year. There is never enough time to catch up one-on-one (or even many-on-many) among the events of the days. It’s both the best and worst part of attending a conference where your colleagues are also friends. You’re left wanting more time, more conversation, more connection. Many conversations and much of the friendship continues over various forms of social media, which I have a very deep attachment to and which has helped me make it through these years of instability and separation from people I care about. Some people regard social media or blogs (like this one) as a stand-in or poor substitute for the intimacy of real-world friendships. But for someone like me who became a teenager at the same time instant messaging apps came into existence (shoutout to AIM!) and who has had the repeated experience of developing a friendship or a friend group only to have to bid farewell to its members they are a godsend. They are a conduit for intimacy, fostering it but not replacing it.

At this conference I had the unusual and somewhat surreal experience of having people–some of whom I knew well, some of whom only in passing or from Twitter, some not at all–reach out and thank me for writing and sharing so much of myself. Some of them had been through something similar, either on their own or with a loved one. Others hadn’t but wanted me to know that my experience had affected them and that they were on my side, hoping along with me for things to get better. I was moved almost to tears several times because, in that way that happens when you write and then post into the void, I wasn’t sure anyone was listening. But they were and responded with manifold kindness. It seemed somehow symbolic of my experience with the academic profession overall. It can seem cold and empty, as we are all separated by space and time (especially the lack of it). And when we speak into it not as a professional academic but as a person the likelihood of getting any response, let alone a positive one, seems so slim.

That is, I think, why revealing so much of myself on here seemed somewhat risky to me and would to many people. We cultivate very carefully our professional selves, even in casual interactions, because the line between the personal and the professional is so blurry in academia. Often we use this fact to impute great skepticism to our readers (our colleagues); better not to show any vulnerability in case someone, some day, may want to hire you and who would want to hire a vulnerable human being? But in this case I’ve seen the other side of that grey area. I found a wealth of empathy where I did not expect it. And that as much as anything has made me want to keep working, to keep writing, to stay in this academic community. Your continued and continual support has really sustained me.

I do recognize, however, that one reason I’m able to share all this is that I have a secure job. I think I would still be posting about my experience in any case simply because it isn’t in my nature not to share thoughts on the most important thing in my life. But I also know that it’s my privilege to be able to do so, to even have the choice. And it is a choice that I have made in smaller ways in the past too. I still recall several years ago during one of my turns on the academic job market when I received an unsolicited email from someone I did not know (although we had a friend in common) informing me that my Twitter account was unprofessional and that I was likely writing myself out of a job. Of course, I cracked my knuckles and wrote a pointed reply about how I had quite literally written a dissertation on the concept of the public sphere and thought very carefully about what I wanted to put in public or not and, what’s more, that it was only for me to decide and not for him to arbitrate. (For the record, I do not consider my account “unprofessional” since it is a purely personal account from which I sometimes tweet about work-related things. Also for the record, this person wrote back with an apology.) But that fear, stoked by incidents like that, would keep many junior people (or even senior people) from publicly showing their wounds–literal and figurative–in a situation like this.

I am glad to be able to speak. I am more than glad that someone is listening. As I return home from the conference, prepared to resume chemo again on Thursday, I feel sadness and trepidation, sure, but I do also feel energized and supported, raised up by a larger community of far-flung friends, colleagues, acquaintances; people I’ve never met face-to-face and people who are an integral part of my daily life.

Friends, academics, Shakespeareans, you are a wonderful bunch. Thank you for making this trip and this conference an occasion to recharge and return to fight another day.

I found myself in the hotel bar somewhere in the neighborhood of 2am on Sunday morning, quite literally weak in the knees from so much dancing, guzzling water and keeping company with colleagues who I’ve come to call friends as we all, exhaustedly, said repeatedly “we should go to bed” and subsequently did not. There was a real last-day-of-camp vibe that infused the whole thing with preemptive nostalgia for the time–so soon!–when we would not be together in the same place. This is the thing about assembling in person only for a few days every year. There is never enough time to catch up one-on-one (or even many-on-many) among the events of the days. It’s both the best and worst part of attending a conference where your colleagues are also friends. You’re left wanting more time, more conversation, more connection. Many conversations and much of the friendship continues over various forms of social media, which I have a very deep attachment to and which has helped me make it through these years of instability and separation from people I care about. Some people regard social media or blogs (like this one) as a stand-in or poor substitute for the intimacy of real-world friendships. But for someone like me who became a teenager at the same time instant messaging apps came into existence (shoutout to AIM!) and who has had the repeated experience of developing a friendship or a friend group only to have to bid farewell to its members they are a godsend. They are a conduit for intimacy, fostering it but not replacing it.

At this conference I had the unusual and somewhat surreal experience of having people–some of whom I knew well, some of whom only in passing or from Twitter, some not at all–reach out and thank me for writing and sharing so much of myself. Some of them had been through something similar, either on their own or with a loved one. Others hadn’t but wanted me to know that my experience had affected them and that they were on my side, hoping along with me for things to get better. I was moved almost to tears several times because, in that way that happens when you write and then post into the void, I wasn’t sure anyone was listening. But they were and responded with manifold kindness. It seemed somehow symbolic of my experience with the academic profession overall. It can seem cold and empty, as we are all separated by space and time (especially the lack of it). And when we speak into it not as a professional academic but as a person the likelihood of getting any response, let alone a positive one, seems so slim.

That is, I think, why revealing so much of myself on here seemed somewhat risky to me and would to many people. We cultivate very carefully our professional selves, even in casual interactions, because the line between the personal and the professional is so blurry in academia. Often we use this fact to impute great skepticism to our readers (our colleagues); better not to show any vulnerability in case someone, some day, may want to hire you and who would want to hire a vulnerable human being? But in this case I’ve seen the other side of that grey area. I found a wealth of empathy where I did not expect it. And that as much as anything has made me want to keep working, to keep writing, to stay in this academic community. Your continued and continual support has really sustained me.

I do recognize, however, that one reason I’m able to share all this is that I have a secure job. I think I would still be posting about my experience in any case simply because it isn’t in my nature not to share thoughts on the most important thing in my life. But I also know that it’s my privilege to be able to do so, to even have the choice. And it is a choice that I have made in smaller ways in the past too. I still recall several years ago during one of my turns on the academic job market when I received an unsolicited email from someone I did not know (although we had a friend in common) informing me that my Twitter account was unprofessional and that I was likely writing myself out of a job. Of course, I cracked my knuckles and wrote a pointed reply about how I had quite literally written a dissertation on the concept of the public sphere and thought very carefully about what I wanted to put in public or not and, what’s more, that it was only for me to decide and not for him to arbitrate. (For the record, I do not consider my account “unprofessional” since it is a purely personal account from which I sometimes tweet about work-related things. Also for the record, this person wrote back with an apology.) But that fear, stoked by incidents like that, would keep many junior people (or even senior people) from publicly showing their wounds–literal and figurative–in a situation like this.

I am glad to be able to speak. I am more than glad that someone is listening. As I return home from the conference, prepared to resume chemo again on Thursday, I feel sadness and trepidation, sure, but I do also feel energized and supported, raised up by a larger community of far-flung friends, colleagues, acquaintances; people I’ve never met face-to-face and people who are an integral part of my daily life.

Friends, academics, Shakespeareans, you are a wonderful bunch. Thank you for making this trip and this conference an occasion to recharge and return to fight another day.